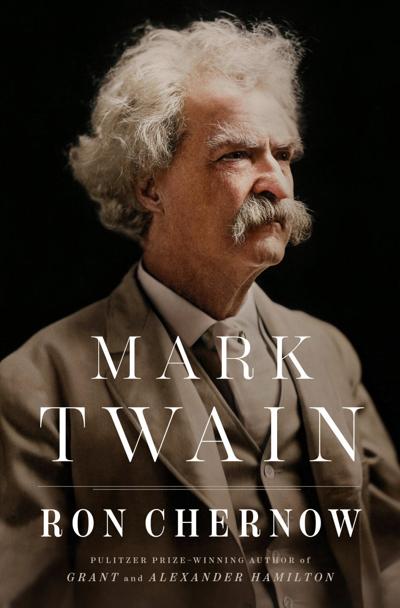

”Mark Twain,” By Ron Chernow. Publisher: Penguin, 1,174 pages. $45.

It’s said that when “War and Peace” was finished and about to be published, Tolstoy looked at the huge book and suddenly exclaimed, “The yacht race! I forgot to put in the yacht race!” At 1,174 pages, Ron Chernow’s “Mark Twain” is essentially the same length as “War and Peace,” but seemingly nothing has been overlooked or left out. Normally, this would be a signal weakness in a biography — shape and form do matter — but Chernow writes with such ease and clarity that even long sections on, say, Twain’s business ventures prove horribly fascinating as the would-be tycoon descends, with Sophoclean inexorability, into financial collapse and bankruptcy.

Overall, Chernow’s “Mark Twain” is less a literary biography than a deep dive into “the most original character in American history.” Born in 1835, Samuel Langhorne Clemens, who adopted the pen name Mark Twain, was by turns a printer, steamboat pilot, journalist, stand-up storyteller, best-selling author, publisher, political pundit, champion of racial equality and all-around scourge of authoritarianism.

Chernow, the prizewinning biographer of Alexander Hamilton and George Washington, tracks several themes throughout these pages, most notably Twain’s attitudes toward Black people and his gradual transformation from Southerner into Northerner. The book is also imbued with contemporary relevance: Twain’s critiques of his own time often sound eerily appropriate to ours. As Chernow says, Twain foresaw “the marriage of politics and religion in the 20th century and the faddish power of cults to brainwash people” and warned against “the perils of extreme patriotism — how it blinded countries to their own vices and the virtues of others.”

Most of us, whether from English classes or television documentaries, already know the general outline of this profoundly American life. After a boyhood spent in the Mississippi River town of Hannibal, Missouri, the young Sam Clemens began writing for newspapers in Nevada and San Francisco. His tall tale “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” (1865) brought him widespread recognition as a humorist, and “The Innocents Abroad” (1869), a comic account of an organized tour of Europe and the Holy Land, made him famous.

On board the tour’s steamship, the Quaker City, Twain got to know a passenger named Charlie Langdon, who had brought along a miniature ivory portrait of his sister. In due course, following a somewhat rocky courtship, the 34-year-old Twain married the woman in the portrait, Olivia (“Livy”) Langdon of Elmira, New York. He utterly adored his pretty, well-brought-up wife, whose fragile health sadly left her incapable of strenuous activity. In one of his last works, “Eve’s Diary,” Twain movingly summed up all that she had meant to him: As Adam stands beside Eve’s grave, he simply says: “Wheresoever she was, there was Eden.” Though some scholars have accused Livy of prissily censoring Twain’s more controversial opinions, Chernow defends her as both a needed first reader and a calming influence on her husband’s volatile temperament.

In truth, our usual image of Twain as a shambling, easygoing Missouri yarn-spinner largely reflects a carefully thought-out stage persona. Not at all extemporaneous before an audience, Twain memorized in advance every word of his evening shows. As well as sociable, mildly depressive, vengeful, and superstitious, Twain was also surprisingly sophisticated. He learned to speak German and knew some French, loved Sir Thomas Malory’s 15th-century “Le Morte d’Arthur” and counted Thomas Carlyle’s “The French Revolution” as his favorite book. His library contained 3,000 volumes.

Once he married Livy, Twain quickly took to the lifestyle of the era’s one percent. His millionaire father-in-law, who had made a fortune in coal, bought the young couple a mansion, with suitable staff, as their starter home. For the rest of their lives, the Clemenses and their three daughters never lacked or denied themselves any pleasure or purchase. For 11 years, the family lived in hotel suites and villas in various parts of Europe, particularly England and Vienna (where Freud, Gustav Mahler and Theodor Herzl came to see Twain perform). At one point, Livy complained that they were as “poor as church mice,” when the family was residing in Venice in a 28-room villa with a team of servants.

While Twain assailed racial prejudice, antisemitism, missionary fanaticism and human rights abuses in Russia and Africa, for which he deserves all praise, Chernow presents him as fundamentally a safe rebel. He might be outspoken and irreverent, but he generally avoided alienating the well-to-do and powerful with whom he dined and hobnobbed. What’s more, after “Huckleberry Finn,” published in 1885, he seems to have exhausted his artistic genius and henceforth relied on the Mark Twain brand to sell books that were often second rate or didn’t quite work.

For instance, “Tom Sawyer Abroad” (1894) — a tired, watered-down pastiche of Jules Verne’s “Five Weeks in a Balloon” (1863) — reunites Tom, Huck and Jim, but in it, the once-dignified Black man of “Huckleberry Finn” has been reduced to a minstrel-show caricature. Twain appears not to have cared about this dastardly cheapening and betrayal.

Again and again, Chernow demonstrates that Twain — often labeled a realist, at least in his fiction — was a thoroughgoing fantasist. The Hartford, Connecticut, writer and socialite was convinced that his self-owned publishing company and the Paige Typesetter — he invested the equivalent of $10 million in the latter alone — would dominate their markets and generate Andrew Carnegie-like riches. While he did score an early triumph in issuing the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, that bit of luck only sucked Twain further into the delusion that he possessed a natural instinct for business.

In writing early works such as “Roughing It” (1872), the magazine serial “Old Times on the Mississippi” (1875) and “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” (1876), Twain clearly idealizes his own youth, mixing autobiography and tall tales with heaps of rosy-hued nostalgia. Many of his later works actually take the form of wish fulfillments, dreams or thought experiments. “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” (1889) transports its modern-day hero back to the Middle Ages; “The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg” (1899) is a revenge fantasy (and his best short story); and the unfinished novella “The Great Dark” blurs dream and reality in a head-spinning farrago about a microscopic world. In the ambitious but unpublished “No. 44: The Mysterious Stranger,” Twain proffered a formless hodgepodge of farce, satire, love story, proto-science fiction and solipsism. Set in medieval Austria, it features a boy with magical powers who calls himself “Number 44, New series 864.962,” along with clone-like Duplicates or Dream Selves of major characters, cynical observations about religion, various time-shifts, and a shocking revelation in the final chapter. Unfortunately, it’s not anywhere near as good as it sounds. By this time in his life, though, Twain had come to believe in a radical determinism, viewing human beings as mere automatons trapped in a hellish universe.

The older, disillusioned Mark Twain certainly wouldn’t win the annual prize for humor now given in his name. It’s even doubtful that Twain would win for his early comic sketches and essays, which now often seem prolix, hokey or bathetically lame. For modern readers, his sharp-edged one-liners, extracted from talks and polemical pieces, demonstrate his wit at its best: “Suppose you were an idiot. And suppose you were a member of Congress. But I repeat myself.”

So why do people sometimes call Twain America’s greatest writer? Mainly because of “Huckleberry Finn.” Its radically demotic style broke with formal British English and captured the sound of living American speech. The novel’s prose, moreover, can be heartbreakingly beautiful, as in the lyrical descriptions of the Mississippi River, while its scurrilous characters (especially the King and the Duke) are a joy forever. That same book has also long served as a flash point in the ongoing history of race relations in America.

To this day, Twain provokes criticism for his recurrent use of the n-word, admiration for his sensitive portrayal of Jim, and cheers for Huck’s thrilling affirmation that he would rather go to hell than turn his Black friend in to the law. Not least, “Huckleberry Finn” is a highly teachable book, one guaranteed to elicit spirited discussion and argument. It remains a vital, completely unsettled text.

In general, the first half or two-thirds of Chernow’s biography resembles a classic rags-to-riches success story. But once Twain’s publishing company and the Paige Typesetting machine go bust, he is forced to embark on a grueling worldwide speaking tour to repay his creditors. Far worse soon comes.

Twain’s eldest daughter, Susy, suddenly dies in 1896 from bacterial meningitis at age 24; his middle daughter, Clara, suffers a psychological breakdown (but recovers); and his youngest daughter, Jean, develops epilepsy and is confined to a sanatorium. Then, in 1904, Livy, after a long decline, succumbs to heart failure.

No longer a Horatio Alger Jr. success story, more and more Twain’s life takes on the lineaments of a soap opera or even a sinister, sensation novel by Wilkie Collins. He hires a secretary who coddles him and secretly hopes to take Livy’s place. When that doesn’t happen, she drives a wedge between Twain and his daughters and begins to appropriate cash from the household reserves. A smooth operator, whom the naive Twain counted as a friend, even tricks him into signing away power of attorney to his financial affairs. Then, in 1909, Jean is found dead in the bathtub.

As he enters his 70s, the lonely writer begins to seek out the companionship of young girls between the ages of 10 and 16. While no sexual overtures accompany these relationships, Twain’s letters to his many “angelfish” are distinctly flirtatious, and the whole business feels more than a little creepy. Once the girls reach 16, he drops them.

Mark Twain once famously quipped that “reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated.” But when he did die in 1910, from a heart attack at age 74, there was no need to exaggerate the worldwide outpouring of love for the man and his work. He was buried in one of his trademark white suits.

For all its length and detail, Chernow’s book is deeply absorbing throughout and likely to succeed the excellent earlier lives by Justin Kaplan and Ron Powers as the standard biography. More than ever, Twain continues to be a touchstone for American writers — witness Percival Everett’s “James,” this year’s Pulitzer winner for fiction. The Library of America even publishes “The Mark Twain Anthology: Great Writers on His Life and Works” edited by Shelley Fisher Fishkin. In Fishkin’s own recent book, “Jim,” this eminent scholar surveys how Huck Finn’s comrade has been interpreted through the years by academics, filmmakers, and novelists such as Everett. As for Twain’s own works, visit any big bookshop and you’ll find entire shelves displaying the best known of them: I recently counted 19 different editions of “Tom Sawyer” at the Beaverton, Oregon, branch of Powell’s bookstore.

All of which said, Chernow’s “Mark Twain” does underscore how dangerous biography can be: While knowledge of Twain’s life can enhance our understanding of his writing, the man himself turns out to have been self-centered, loving but neglectful of his daughters, foolishly gullible, something of a money-hungry arriviste and vindictive to a Trumpian degree. Of course, he was also a genius — at least in a small handful of books, perhaps only one really. Were it not for “Huckleberry Finn,” would we really think of Mark Twain as one of America’s greatest writers? I wonder.