The abandoned homes of Venezuelan migrants

The massive exodus has given rise to a new service: clearing out the homes of those who have decided they’re not coming back

There are houses with beds that haven’t been slept in for years. Others, where the bottom of a cup of coffee — drunk just before leaving for the airport — has hardened into a kind of bitumen and stifled any plans for a return trip. In nearly all of them, dust has formed stubborn knots on the furniture and walls, making them difficult to remove.

The house where Mairin Reyes is, on a Wednesday before Easter Week, is an annex of a main residence in a middle-class neighborhood in the southeastern part of Caracas, on a street with private security, where the children and grandchildren of a family that is no longer in Venezuela once grew up.

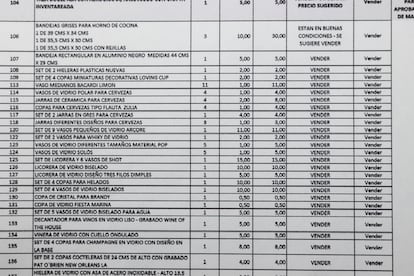

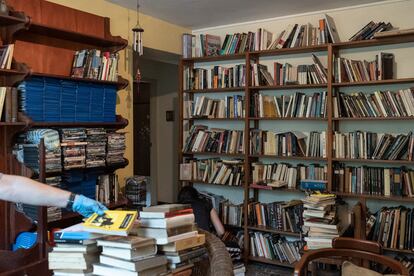

She has 15 days to empty out this house, which is attached to another one that she has already cleared. It’s enough time to dismantle bookcases, tear up old papers — a part of her job that has become a liberating ritual — deep clean, give away kilos of old clothes and junk that no one wants to keep, and create an inventory on Excel of the items that will remain in her custody to be sold later on behalf of their owners. Once empty, the house will be demolished by its new owners, who plan to build a new one.

Venezuela has experienced a massive exodus in the last decade and a half, with nearly eight million people estimated to have left, according to the United Nations. The displacement of Venezuelans — one of the largest in the world — has been driven by a prolonged democratic crisis that seems endless and an economic recession that has reduced the country’s oil-dependent GDP by a third.

Beyond the country’s borders, the exodus has put pressure on neighboring countries, which have taken in migrants to the point where Venezuelans are now in the spotlight of U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration and its deportation policies. Inside the country’s borders, much remains to be done with the things and places left behind by those who have gone.

Amid the exodus, Mairin, 65, has begun a business — Soluciono Por Ti (I Solve It For You) — with a service that, she argues, is much more than helping people move houses that will become their own.

“We support the owners to help them make decisions remotely,” she comments during a break from her morning tasks: sorting through papers, scraps of paper, and other items that people accumulate when they believe they’ll never have to leave.

In this house, leaks have destroyed the ceilings of several rooms. But still visible on one doorframe is a pencil mark noting that the child who lived there had grown past 1.2 meters by age eight. In that same room, a toy Batman remains with its arms raised, and in the closet hangs the uniform shirt from the last year of high school, still covered in classmates’ signatures — a testament to the end-of-year ritual celebrated by Venezuelan students.

Carolina Pérez, 60, is accompanying Mairin that morning. They are sisters-in-law. A lawyer turned psychotherapist, Carolina has now found a new way to diversify her income by helping empty out homes.

“You can understand people from the things they leave behind,” she says while sorting through some children’s books in English. “You can tell this was a family very focused on parenting, because they have so many books on the subject.” Later, she finds inside one of the books an ultrasound image confirming a pregnancy.

Migrant history

Mairin’s work is a kind of archaeology of Venezuela’s recent past — the story of the empty Venezuela. It also confirms the findings of migration experts. After being a destination for immigrants — Europeans (especially Italians, Spaniards, and Portuguese), Middle Easterners in the mid-20th century, and Colombians in its later decades — Venezuela began to see waves of its own people departing, starting with Hugo Chávez’s rise to power.

First, the well-off professionals left, then the middle class. Those were the years of expropriations, occupations, and invasions — some carried out under the banner of the Bolivarian Revolution. As a result, many homes and apartments were locked up for years, left in the care of a relative who hadn’t yet left the country, in the hope of better times — times when they could sell, rent, or return. The most recent wave of immigration, in the last few years, has been made up of those who had no choice but to leave on foot or cross the Darién Gap, whose homes fit in a couple of bags.

Capodimonte porcelain flowers, crystal decanters, souvenirs from SeaWorld in Florida or Gaudí’s houses in Barcelona, Hervigon dinnerware, German china, French Limoges tea sets, typewriters, oversized silverware, Venetian masks with fridge magnets, vinyl records featuring music by Enrique y Ana, El Chavo del 8, and The Lady and the Tramp, the bestseller The 8th Habit by Stephen Covey, and enormous book collections that are treasures, cassette players, Discmen, more glasses, goblets, and plates, lots of Barbie dolls, tablecloths and runners — these are the kinds of items that show up again and again in the Excel spreadsheets Mairin has filled out while clearing out over 20 homes and apartments in Caracas. Decorative Murano glass figures are another common item.

“They look like squirrels,” Mairin notes in one of her inventories, shown from the shop she has opened in Guarenas, just outside Caracas, filled with objects once owned by a Venezuelan middle class that has largely vanished.

“This job has allowed me to learn a lot about art and the history of all those items,” says Mairin happily. But she is quick to add, cautiously, that one should never judge her clients: “I don’t want to have so many things, I want to live with only what I need, and if I’m going to eat on beautiful plates, I want to do it every day, not just on special occasions.”

The items her clients always ask her to keep and send to their new countries are family photographs, essential documents like birth or death certificates and divorce decrees, and personal keepsakes — such as a small silver box from a baptism. But she has also mailed a person’s ashes to Colombia and, more recently, shipped a piano to Spain. This ability to manage all the complexities that can arise when clearing out a home, Mairin says, is what sets her service apart from other similar businesses now appearing in the market.

Square meters to spare

Just as objects pile up in Mairin’s secondhand shop, vacant properties are stacking up across the city. Since 2014, home prices have dropped by 50% compared to their original purchase price — another scar left by Venezuela’s onoing crisis. The Metropolitan Real Estate Chamber estimates that there are at least 3,000 unoccupied homes in the capital alone, in addition to some 600,000 square meters of available office space, over one million square meters of industrial space, and a surplus of 200,000 square meters of retail space in shopping centers — where not all stores manage to open and others do so with great difficulty.

The city of Caracas — even as it receives migrants from other regions of the country where the crisis in basic public services is more acute — has become too large for the number of people who actually live and work there. Housing demand has dropped — or more precisely, the ability to purchase housing has declined, as the government has sacrificed access to credit in an effort to curb inflation. The rate at which existing inventory is being absorbed is so slow that, according to industry estimates, it could take 25 years to sell what is currently on the market. This is what real estate agents call a “complex market.”

Under current conditions — which experts expect to deteriorate further due to ongoing political instability, the reimposition of sanctions, and a looming recession — the real estate business is becoming increasingly difficult.

“It can take more than a year to sell a property that costs more than $50,000. It becomes a struggle between the agent and the owner to lower the price until it’s attractive,” says Martín Fernández, vice president of the Metropolitan Real Estate Chamber.

Yet properties listed for millions of dollars still appear in flashy Instagram reels from real estate agents — posts that occasionally go viral out of sheer disbelief or outrage. In the Venezuelan context, Fernández warns, these listings are red flags. “Selling a property worth more than a million dollars can bring serious complications due to money laundering,” he cautions.

Despite the challenges, some people continue to build as a way to anchor their capital — even though the construction sector is at its lowest point. In some cases, new buildings are being erected on top of demolished houses. But it’s the lower-cost properties, in peripheral or depreciated areas of the city, that are seeing the most movement.

“The available apartments are a certain age — around 30 or 40 years old — so they require repairs, adjustments, and updates,” explains Fernández, who is also an urban planner. “Many of those who emigrated left their properties locked up in the care of a relative, and most of those migrants are not planning to return, as they’ve already settled elsewhere. That’s why they’re now selling.”

“Today, deciding to sell a home is a psychological decision,” he adds, “because it means accepting the loss of value and acknowledging that the property they once lived in or bought as an investment is not going to appreciate.”

Some of the homes that fail to sell and flood the market also end up becoming a problem for the neighborhood. In vacant houses, as Mairin has witnessed firsthand in many of her jobs, pipes can burst the moment a faucet is turned on. Vacant homes don’t withstand the passage of time.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.