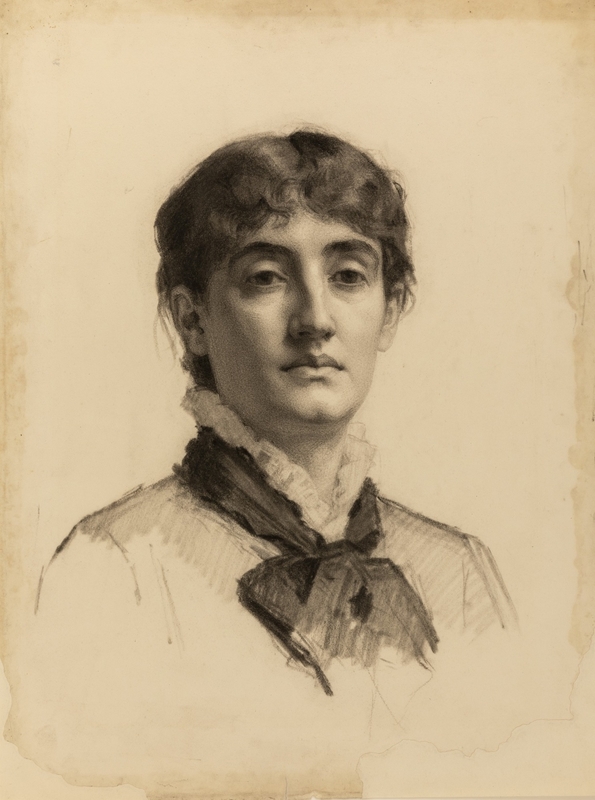

Mary Moser RA (1744–1819) is both one of the most famous women artists of the eighteenth century and at the same time a bit of an enigma. Elected a founding member of the Royal Academy at just 24 – one of just two women to be Academicians until the mid-twentieth century – her surviving works seem to only hint at her rich artistic life.

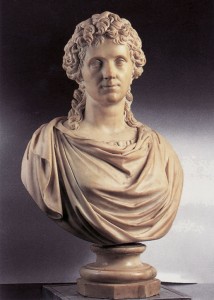

Mary was born into an artistic family in London. Her Swiss father George Michael Moser was an artist, gold chaser and drawing tutor to George III while her mother Mary was the daughter of Claude Guynier, a French painter.

By the age of fifteen Moser had won a five-guinea premium and a silver medal with merit at the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturing & Commerce (known as the Royal Society of Arts), for a floral watercolour. She continued to exhibit annually with the Society while embarking on a successful career as a flower painter.

Before examining Moser's flower paintings in more detail, it is important to consider the botanical and historical context of this aspect of her work. In the eighteenth century, it was widely considered that there was a hierarchy of painting genres. Flower painting – and still life more generally – was seen as the lowliest of the genres, with history paintings and portraiture at the apex.

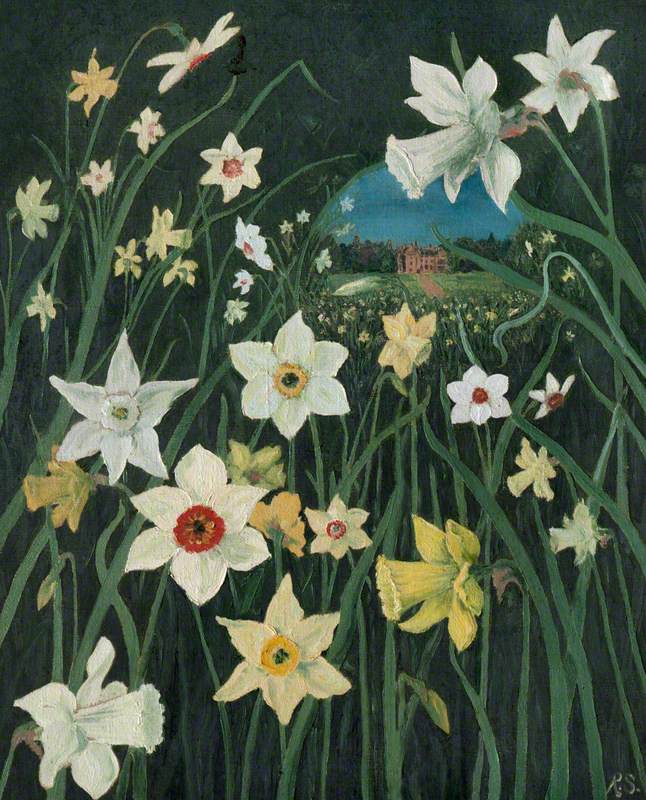

However, there was also a growing passion for plant collecting among the wealthy in this period, first seen in Holland and then Britain. Many great gardens were laid out in the grounds of stately homes by new landscape designers and this led to a high demand for flower paintings. It is clear from Moser's works that she clearly had access to these latest botanic imports and discoveries, showing the elite social circles in which she moved.

Early in her career, Moser painted a series of allegorical paintings featuring the signs of the zodiac. Today, six of these are in the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge and two in the Lady Abingdon Collection at the V&A.

They have impeccable provenance, being mentioned in the will of Mary, Countess of Lowther (daughter of Lord Bute), in which she bequeathed thirteen watercolours to her nephew. Like her father, Mary Lowther was a keen gardener and connoisseur and it is likely that Moser obtained some of her specimens from her patron and friend's garden at Broom House near Fulham Palace.

Each of the watercolours features an arrangement of flowers appropriate to the ascendancy of the zodiac sign. The flowers are displayed in an urn or vase decorated with the relevant sign surrounded by classical swags and acanthus leaves.

The earliest of the set in the Fitzwilliam collection is from 1765 and focuses on Gemini (21st May – 21st June).

Image credit: Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

An urn decorated with the sign of Gemini

Containing tulips, crown imperial, lilac, roses, a lily and narcissus, 1765, graphite, pen and ink, watercolour and bodycolour on paper, prepared with a dark ground by Mary Moser (1744–1819)

Moser has chosen vibrant blooms which represent the species that would be flowering in late spring and early summer – notably rarities (for the time) include varieties of tulips and the unusual Fritillaria imperialis imported from Asia.

The works in the Fitzwilliam are all categorised as drawings, requiring precise draughtsmanship. Capricorn (dated 1765) and Sagittarius (dated 1768) both contain flowers representative of the winter months including hellebores and rare imported Amaryllidaceae.

The three remaining Fitzwilliam works are representative of Pisces, Aries and Libra.

Image credit: The Fitzwilliam Museum

Mary Moser (1744–1819)

The Fitzwilliam MuseumThe first two display flowers which bloom in early spring and high summer, many of which – like the hibiscus, anemone and delicate jonquils – were brought from the Netherlands. Others would have been gathered by professional plant hunters from over the world.

In contrast to the brighter colours of spring and summer Moser's Libra shows a more autumnal palette.

Image credit: Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

On a stone ledge an urn ornamented with the astrological symbol for Libra

Contains an arrangement of flowers including hibiscus, a campanula, delphinium and nasturtiums, 1765, graphite, pen and ink, watercolour, bodycolour including white and gum Arabic on paper, prepared with a dark ground by Mary Moser (1744–1819)

Lit from the right rather than her customary left – as if to highlight the shortening days of autumn – she has chosen rare cream and russet hibiscus, offset by tiny blue star-of-Bethlehem.

The zodiac signs of Cancer and Virgo are in the V&A, with the same provenance. They contain blooms representative of high summer. It is assumed that this series was a commission as Moser continued to paint numerous other works during this period.

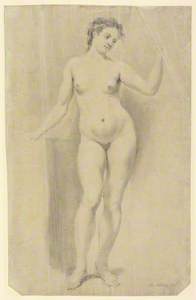

One of Moser's early works is a drawing of a female nude, and its existence (and survival) is quite unusual.

Probably made between 1762 and 1768, the model is depicted in relaxed position, standing in the contrapposto position – one leg bears the weight and the other bends slightly at the knee allowing the body to turn elegantly.By drawing this pose, Moser was displaying her knowledge of classical works – essential for an artist's education at the time.

However, the work is particularly unusual as women were not normally permitted to attend life drawing classes at this time, supposedly for reasons of modesty. As with so much of Moser's output, we don't know how she gained access to a nude model – perhaps her father, a staunch believer in life drawing, arranged for someone suitable. Or perhaps (as other artists were known to have done) she used a mirror and her own body. We may never know.

1768 was a landmark year in the British art world, as George III gave his long-awaited blessing to the creation of the Royal Academy (RA). 34 initial members were elected, including George Michael Moser, Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, Nathaniel Dance, Benjamin West, Richard Wilson, and two women – Mary Moser and Angelica Kauffmann.

From this point, Moser signed her paintings 'Mary Moser RA.' One of the conditions of membership was that members should exhibit their work in the RA's annual June exhibition, initially at Pall Mall and, from 1780, in their new home in Somerset House, designed by Sir William Chambers. As its first Keeper, Moser's father George Michael Moser and his family had luxurious rooms there, giving Mary access to the daily business of the Academy.

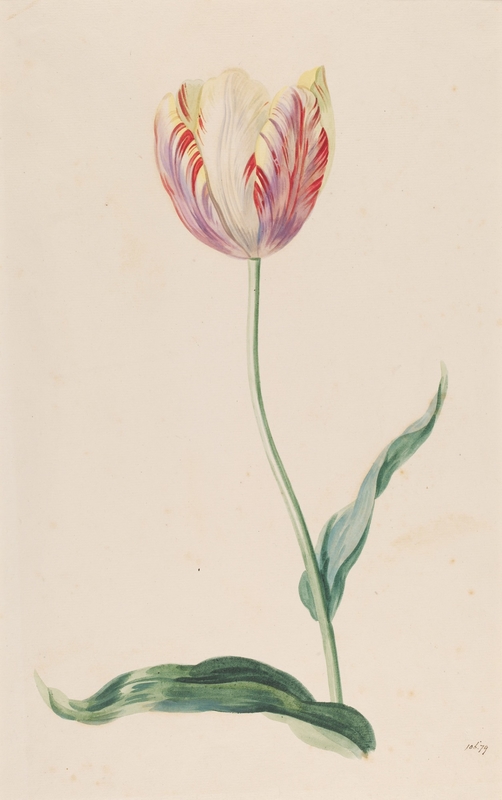

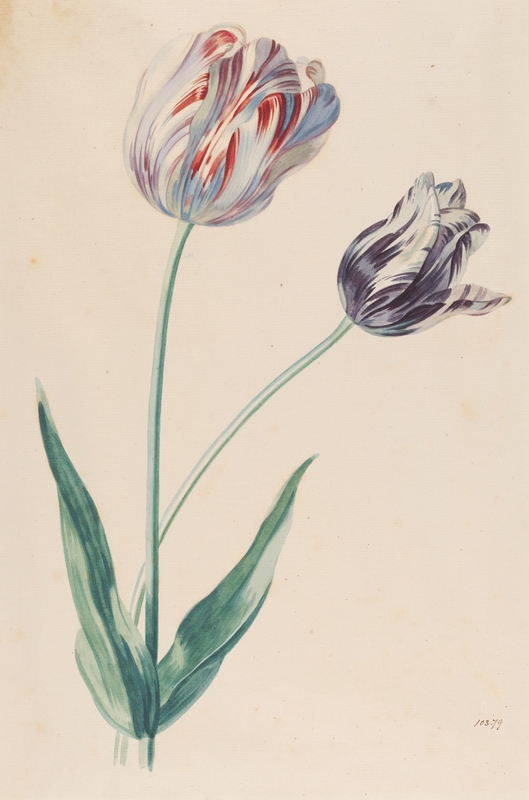

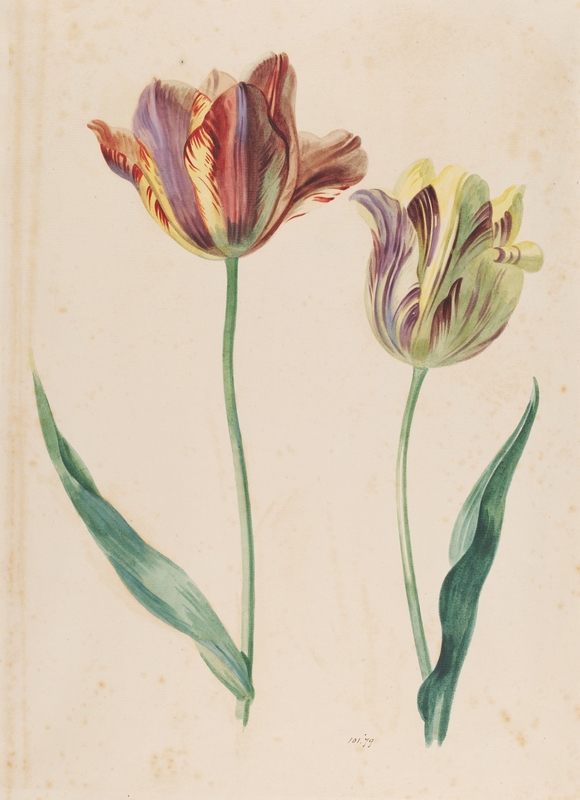

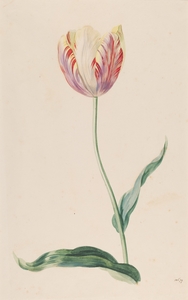

Although they are undated, Moser produced a series of tulip watercolours probably between 1764 and 1800, eight of which are held by the V&A. These are studies of rare, variegated blooms which could well have been used as teaching aids – Moser was also a tutor of drawing.

Some of Moser's drawings were made as preparatory drawings for an embroidery. We know that her artwork was used for this purpose – in 1772 Queen Charlotte commissioned an opulent state bed, now at Windsor Castle, with a tester, hangings, chairs and stools to match, richly embroidered with swags of flowers.

The makers were from Mrs Phoebe Wright's Celebrated Establishment or School for Embroidering Females. The women there were orphaned or impoverished, and we know that Moser provided the botanical designs from which the school's embroiderers worked.

Moser continued to find favour with the royal family. She was commissioned by George III to design the floral canopy above the throne at Windsor Castle, but her most important work is the garden room at Frogmore House, Windsor. Bought by the King for his wife and daughters, it provided a daytime escape for them as he slipped into mental illness. Started in 1792, the room is completely covered in painted floral designs, together with seven oil paintings and a stunning ceiling. It is now known as The Mary Moser Room.

Moser was clearly close with the royal family. In a diary entry from 1797 Joseph Farington claimed that she was drawing mistress to the Queen and her daughters for several years and even that they rose at four in the morning in eagerness to pursue their studies.

However, apart from this entry, there is no evidence that she taught them drawing – as with much of Moser's life, the facts are hard to pin down.

We do know that Moser had an affair with the artist Richard Cosway, but in 1793 she married Captain Hugh Lloyd. She ceased to be a professional artist, but still exhibited under her married name of Mary Lloyd. She fulfilled her duty as an Academician latterly by attending meetings and voting on Academy matters. She continued to show her work at the RA summer exhibition until 1802.

Perhaps surprisingly when looking at the works that have survived, among the numerous flower paintings she exhibited were a similar number of works featuring the human figure. Some were portraits, while others were fashionable history paintings with titles such as The Muse Erato. Moser was well read and selected heroines and scenes from fashionable gothic romances and classical writing as her subjects.

Sadly none of these figurative pieces survive – or more likely, some have been misattributed over the years either as 'unknown artist,' 'British School,' 'British (English) School' – or even attributed to other artists.

Moser was known to be short sighted and this is the usual reason given for her retirement. However, in December 1810, Farington recorded in his diary that she 'was confined to Her bed, having had a paralytic stroke.' Although she recovered, it left her weakened down one arm and is a more likely reason for her retirement.

Moser died in her London home on 2nd May 1819 aged 74 – famous, often referred to as lively and chatty, and greatly admired in her time. Since her death she has become a much more shadowy figure, her reputation resting on the flower works which dominate the existing oeuvre attributed to her.

Comparing her reputation with that of her contemporary Angelica Kauffmann, it seems that the eighteenth-century idea of a hierarchy of genres perhaps still holds – Kauffmann's history and mythological paintings still seem to fascinate the public, whereas Moser's flower paintings are still neglected.

It's possible that in future more works by Moser may be identified, and her list of extant works expanded. However, even in the existing works that remain, her draughtsmanship and artistry are to be admired.

Jenny Head, freelance art historian

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation